An authentic explosion would appear and continuously enlarge. Video of this DEW Attack shows an initial explosion that then vanishes but then re-appears, like so many other DEW Attacks. Also incredibly suspicious: Yet another: Perfectly-lit; perfectly-aimed-and-framed; perfectly-timed video in Zapruder-2.0 fashion further indicates foreknowledge, planning of the takedown.

Evidenced across DEW Attacks is an initial hit, then slight, brief subsidence, and then the resulting, desired energetic explosion. This is the presumed signature of one form of the militarized Directed Energy Weaponry described in 1983 by President Reagan regarding his “Star Wars” program called “Strategic Defense Initiative” (SDI).

Consider also the extremely highly motivational reality of the then recently-revealed US Naval dumping of nuclear waste at the Farallon Islands just 20 miles west of San Francisco Bay. Was Fukushima in some part a “cover” for the expected revelation of contamination? See below for this deep research.

Frame immediately prior to Initial Hit

Initial Hit

Attack is nearly always from the top-down.

Slight gain in Initial Hit Explosion

Hallmark “dropping-away” of Initial Hit as its energy dissipates

Continued DEW Hallmark unlikely “dropping-away” – a genuine explosion would continue expanding, it would not drop away

Energy balance evens out – the Curious Impossibility – Here is the “smoking gun” video evidence proving there was not one explosion but two

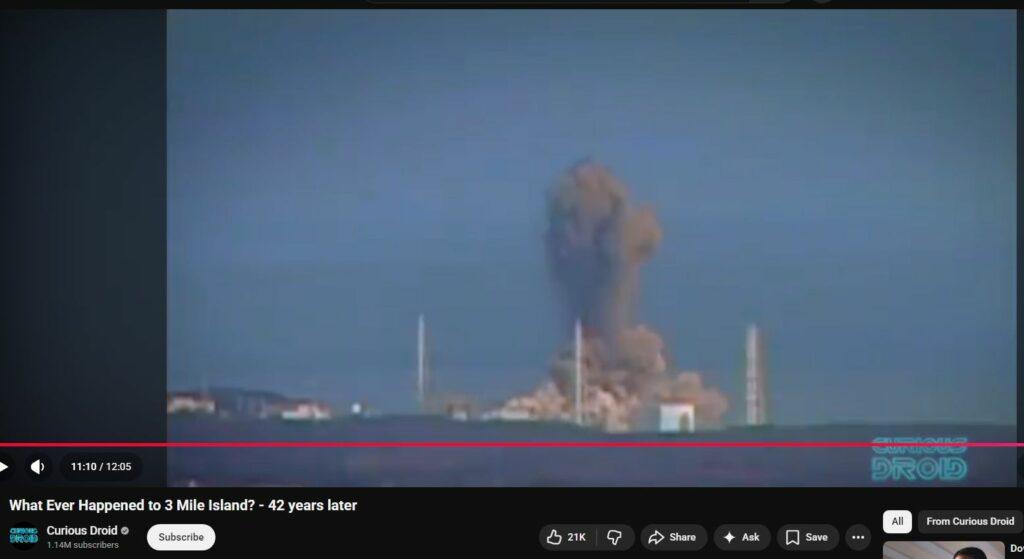

Then the secondary Explosion begins

Raging secondary explosion

Mammoth

Legacy of Nuclear Waste Dumping at the Farallon Islands

Background and Timeline: From the mid-1940s until 1970, the waters off San Francisco – near the Farallon Islands (~30 miles west of the Golden Gate) – served as an official dumping ground for U.S. nuclear waste. This practice began shortly after World War II (with initial dumping reported in 1946, and possibly late 1945) under the authority of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). The primary agent carrying out the dumping was the U.S. Navy, notably through its Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) based at Hunters Point Shipyard in San Francisco. Other institutions, including nuclear research labs (e.g. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory), also sent radioactive debris to be disposed at sea. For 30 years – until ocean disposal of radioactive waste was halted by policy in 1970 – an estimated 47,500 steel drums (mostly standard 55-gallon barrels) and other containers of low-level radioactive waste were consigned to the depths near the Farallon Islands. This makes the Farallon Islands site the first and largest offshore nuclear waste dump in U.S. historyatlasobscura.com.

Dumping Operations and Methods: The waste materials originated from military and industrial nuclear programs and were generally low-to-medium level radioactive byproducts: contaminated laboratory materials, tools, ship decontamination residues, and other debris. The NRDL, tasked with handling fallout-contaminated ships and equipment from atomic tests (e.g. Operation Crossroads at Bikini Atoll), played a central role. For example, the aircraft carrier USS Independence – heavily irradiated during the 1946 Bikini tests – was towed to Hunters Point for study and decontamination; after efforts to scrub it failed, the Navy packed the vessel’s hull with additional radioactive waste and scuttled the entire ship in the Farallon dumping zone in January 1951. (The wreck of USS Independence now rests upright under ~790 m of water, rediscovered in 2015.) Aside from scuttling contaminated ships, the routine disposal method was to ship boxed or drummed waste to Hunters Point, load it onto barges, and transport the barges out to sea near the Farallones. Each drum was typically filled with concrete or scrap to serve as ballast, and then cast overboard. In practice, not all drums obediently sank; reports indicate that barrels which bobbed to the surface were sometimes shot with rifles by Navy personnel to puncture and sink them. By 1970, when the dumping ceased, roughly 14,500 curies (≈540 TBq) of radioactivity had been consigned to the ocean floor in this areacommons.wikimedia.org. Much of the radioactive inventory was in short-lived isotopes that decayed substantially over ensuing decades – by EPA estimates, most of the radioactivity had decayed by 1980 – but long-lived transuranic elements remain present.

Map of the Gulf of the Farallones showing approximate locations of the nuclear waste dumping sites off San Francisco. Site A (shallow, ~90 m depth) received ~150 drums in 1946, Site B (intermediate, ~900 m depth) ~3,600 drums, and Site C (deep, ~1,800 m depth) ~44,000 drumspubs.usgs.gov. The orange triangle outlines the general region of the Farallon Islands Radioactive Waste Dump (FIRWD), over which barrels are scattered.

Dump Sites and Locations: Three designated dump sites (often labeled Sites A, B, and C) were used, corresponding to different distances and depths west of San Francisco. Site A, used briefly in 1946, lay on the continental shelf in only ~90 m (300 ft) of water and received an estimated 150 drums. Site B was on the upper continental slope (~900 m or 3,000 ft deep) and received on the order of 3,000–4,000 drums, especially in the late 1940s and 1950s. The primary dumping ground, Site C, was at ~1,800 m depth (approximately 5,900 ft) on the continental slope, about 30–40 miles offshore; the vast majority of the waste – roughly 44,000 containers – were sent to this deep location. The nominal coordinates of the two main sites are roughly 37°37′N, 123°17′W (for Site C, the deep 1,800-m area) and 37°38′N, 123°08′W (for Site B, the 900-m area). In practice, many drums missed their target drop zones due to inclement weather or navigation limits. Instead of neat piles at the intended coordinates, the barrels ended up littering a broad swath of seafloor. Surveys indicate the debris is scattered over an estimated 1,400 km² (~540 mi²) area of the ocean floor – an area about the size of Los Angeles – now falling within the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuarypubs.usgs.gov. Notably, not all wastes were documented: besides radioactive matter, other hazardous wastes (e.g. surplus munitions, chemical agents, mercury, cyanide, and industrial acids) were also dumped in these waters during the mid-20th centurysanctuaries.noaa.govpubs.usgs.gov, though their exact quantities and locations are poorly recorded.

Condition of the Dumped Barrels: Decades after their disposal, the status of the submerged waste containers ranges from intact to completely disintegrated. Early examinations were sporadic – for instance, a 1974 submersible dive found only a few clusters of drums, and one drum was retrieved in 1976 for analysis. Beginning in 1990, more systematic surveys were undertaken by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in collaboration with NOAA and the Navy. By using side-scan sonar mapping to locate metallic objects, then sending submersibles (like the Navy’s DSV Sea Cliff) and remotely operated vehicles, researchers located and visually inspected numerous barrels on the seafloor. They confirmed that barrels exist in all stages of degradation: some are **“completely intact,” while others are “seriously deteriorated” or have collapsed in on themselves. Underwater video shows, for example, drums with rusted-out sections or imploded tops. In many cases only slumped metal or a halo of displaced sediment marks where a barrel once lay. This heterogeneity is expected given the drums’ thin steel construction and the corrosive saltwater environment over 50–70 years. The exact number and location of all containers remain unknown – thousands have been mapped, but many likely lie buried in sediment or beyond survey areas. Federal agencies have concluded that attempting a cleanup (i.e. dredging up the barrels) could pose greater risk (through spreading contamination) than leaving them undisturbed on the sea floor. Thus, the strategy has been one of in situ monitoring rather than removal.

Environmental Monitoring and Radiological Measurements: Given understandable concern about leaking radioactive waste, scientists have periodically assessed water, sediment, and marine life around the Farallon dump. In the late 1970s, preliminary studies (e.g. by Lawrence Livermore Lab) measured radionuclide levels near the dump and found contamination consistent with global fallout but not dramatically above background. By the 1980s and 1990s, more sensitive analyses revealed subtle signs of leakage. A comprehensive study in 1986–87 sampled deep bottom-feeding fish (like Dover sole, sablefish, thornyhead) caught near the dump sites, as well as mussels from Farallon intertidal zones, and compared them to reference samples from a distant control site. The concentrations of radionuclides such as cesium-137, plutonium-238, plutonium-239/240, and americium-241 in the fish were generally low – on the order of a few becquerels per kilogram wet weight – and not statistically higher at the Farallon site than at the control site. This suggested that at least by the 1980s, measurable contamination in local biota was diffuse rather than localized. However, the types of radioactive elements and their ratios provided clues of the dump’s fingerprint. Notably, Farallon-area fish showed elevated proportions of plutonium-238 and americium-241 that are inconsistent with global nuclear test fallout. The ratio of Pu-238 to Pu-239+240 in these fish was about 4.0 – nearly 100× higher than the Pu isotope ratio in worldwide fallout (≈0.03) – indicating a source term richer in Pu-238. Americium-241 (a decay product of Pu-241) was also comparatively high (Am-241/Pu-239+240 ratio ~30, vs ~0.4 in global fallout). These anomalous isotope signatures strongly imply a local source of transuranic nuclides – consistent with leaking waste barrels, since laboratory wastes and fuel byproducts in the mid-20th century often contained Pu-238 and other isotopes not prevalent in open-air weapons fallout. Indeed, by the 1990s it was acknowledged that some “specter of leaking barrels of plutonium now lurks on the ocean bottom” near San Francisco, to quote then-Governor Jerry Brown’s 1982 testimony to Congress. On a positive note, the absolute levels of radioactivity measured in marine life remain extremely low. The 1990s study estimated that eating Farallon fish would give an adult an annual radiation dose of at most 0.03 millisieverts from americium (and far less from other nuclides) – for context, this is only a few percent of the radiation dose one would get from natural background in a year. While this suggests no acute health threat to humans or wildlife, the presence of any plutonium in the food chain was, and is, cause for continued monitoring.

Known and Potential Impacts: The Farallon nuclear dump’s ecological and public health impacts are difficult to quantify, but to date appear limited in scope. Fears of contamination have at times affected the local fishing industry – for example, in the 1970s there was public concern about consuming fish from the “Radioactive Farallon Gulf,” which depressed the market for a timepubs.usgs.gov. This prompted environmental assessments which, by the late 1990s, concluded that actual contamination of the marine ecosystem was much lower than initially feared. The most persistent impact may be psychological: the knowledge that tens of thousands of radioactive drums lie offshore has cast a shadow over the otherwise rich fishing grounds of the Gulf of the Farallones. Scientifically, aside from the elevated Pu and Am levels noted in some fish tissues, no widespread radiological harm to marine populations has been demonstrated – seabirds, marine mammals, and most fish in the sanctuary do not show radiation levels beyond global-background ranges. It helps that most dumped materials were categorized as “low-level” waste (e.g. lightly contaminated lab trash, not high-level reactor fuel). Additionally, the vast volume of the ocean provides significant dilution. Nonetheless, the Farallon Islands dump remains an environmental hazard in a latent sense: many of the longer-lived radionuclides (plutonium-239 has a 24,000-year half-life; americium-241 ~430 years) will persist in seafloor sediments for millennia, and some drums may yet corrode and release their contents. Ongoing research, including a 1998 joint US–UK survey using towed seabed gamma spectrometers, has sought to map radiation “hotspots” on the seafloor directly above the dump sitespubs.usgs.govpubs.usgs.gov. The Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary (established 1981) continues to support such monitoring. The official stance of agencies like NOAA and EPA is that active remediation is not currently feasible, so the waste is best left buried in sediment – but with long-term surveillance in place.

Secrecy, Records, and Revelations: At the time it was conducted, the Farallon dumping program was not widely publicized, and details about what was dumped were often kept vague or classified. Some operations were outright secret: declassified Navy memoranda from the late 1940s show plans to dispose of radioactive residues “in every harbor on the West Coast” and directives for dumping contaminated solutions quietlytreasureislandcalifornia.wordpress.com. It wasn’t until years later that the full extent became known. In 1980, the EPA produced a “Radioactive Waste Dumping Off the Coast of California” fact sheet acknowledging the Farallon dump and summarizing available datacommons.wikimedia.org. In 1998, a U.S. GAO (General Accounting Office) report to Congress further catalogued the dumping, identifying the sources of the waste and the contractors involved (e.g. the Ocean Transport Company was one firm hired to perform ocean dumping for the AEC in the 1950s)treasureislandcalifornia.wordpress.com. Investigative journalists have also shed light on this dark chapter. A notable exposé was “Fallout” (SF Weekly, 2001) by reporter Lisa Davis, which drew on declassified NRDL records. Her reporting revealed that the NRDL and associated agencies routinely handled and disposed of radioactive materials with lax safety in the Bay Areaen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Among the troubling practices documented: dumping thousands of gallons of radioactive cleaning acids and sand directly into San Francisco Bay (in the late 1940s) after scrubbing bomb test shipsen.wikipedia.org; test-discharging liquid radioactive waste into bay tides to observe dilution; and simply “flushing” highly contaminated residues down drains or into the bay or ocean. Such revelations underscore that the Farallon Islands nuclear dump was part of a larger pattern of post-war nuclear waste mismanagement, facilitated by secrecy and the assumption that the ocean (or bay) could serve as a limitless sink. Community health activists in San Francisco have since linked legacy pollution at Hunters Point (the NRDL site) to elevated illness rates, and point to the Farallon barrels as another legacy that needs accountability. In recent decades, government agencies have become more forthright about these past actions. The Navy has admitted to the “infamous” dumping of tens of thousands of barrels off the Farallones, and the site is now listed in DOE and NOAA records of historical waste sites. Still, because many documents were lost or never created (for instance, the contents of each barrel were not catalogued in detail), there remains an element of uncertainty about the full radiological inventory sitting offshore. The Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump stands today as a sobering historical lesson in the challenges of nuclear waste disposal and the long-term consequences of short-term decisions.

Fukushima Disaster Contamination vs. Farallon Islands Leakage

Radiation in the Pacific after Fukushima (2011–Present): The March 2011 meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant released a pulse of radioactive contaminants into the Pacific Ocean unprecedented in scale for a civilian reactor accident. In the weeks after the disaster, radioactive plumes (airborne and oceanic) dispersed eastward. Traces of Fukushima fallout were measurable along the U.S. West Coast within days to weeks – for example, iodine-131 (half-life ~8 days) was detected in minute concentrations in California precipitation and milk in April 2011. These short-lived isotopes soon decayed away, but longer-lived fission products traveled more slowly via ocean currents. Oceanographers projected that the main body of Fukushima-derived water would reach the North American coast by about 2013–2014. Indeed, by 2013, migrating Pacific bluefin tuna that had crossed from Japan to California carried a detectable signature of Fukushima radioisotopes in their flesh. Tuna caught off California in August 2011 contained on average about 10 Bq/kg of cesium (Cs-137 + Cs-134) attributable to Fukushima – a very low level (far below safety limits) but measurable against the pre-existing background.

By 2014, instruments began to pick up Fukushima-derived cesium in Pacific waters off North America. A monitoring program led by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) announced in November 2014 that it had detected cesium-134 in ocean samples about 100 miles due west of northern California – the first confirmed arrival of Fukushima radioactivity in offshore U.S. waterswhoi.eduwhoi.edu. The concentration was extremely low: about 1.9 Bq/m³ of Cs-134, along with ~3–4 Bq/m³ of Cs-137 (which was already present from 1960s nuclear testing)whoi.edu. This level is more than a thousand times below U.S. EPA drinking water limitswhoi.edu and posed no significant health risk, a fact repeatedly emphasized by scientists. Over the next couple of years, the Fukushima plume continued to dilute and diffuse. By 2016, trace amounts of Cs-134 were detected in shoreline samples along the California coast, though often at or below detection limits (~0.2 Bq/m³)whoi.edu. Projects like “Kelp Watch 2014” also tested coastal kelp for Fukushima isotopes; initial results found none (no Cs-134 above background) in kelp from California through Alaskawhoi.edu. In summary, the timeline was: a rapid but brief atmospheric fallout in spring 2011 (mainly affecting Japan and nearby regions, with only vanishingly small traces in the U.S.), followed by the first ocean plume reaching U.S. offshore waters by late 2014, then continued presence of very low-level Fukushima contaminants in the North Pacific to the present. Importantly, the peak concentrations measured off California were many orders of magnitude below peak levels near Japan. At the Fukushima plant’s discharge point in 2011, ocean cesium levels were astronomically high (tens of millions of times pre-accident levels); by the time that water crossed the Pacific, dilution had reduced contamination to levels barely distinguishable from historical fallout background.

Isotopic Fingerprints – Fukushima vs. Farallon: A key tool in discerning whether detected radiation comes from Fukushima or local sources (like the Farallon dump) is to examine isotopic ratios and the presence of short-lived nuclides. One isotope in particular – Cesium-134 – serves as a clear “fingerprint” of Fukushima. Cs-134 has a half-life of about 2 years, meaning any Cs-134 released in the mid-20th century (e.g. from nuclear weapons tests or the Farallon waste barrels) has long since decayed away. Prior to 2011, Pacific seawater contained no detectable Cs-134, only residual Cs-137 from 1960s bomb testing. Fukushima, however, released Cs-134 in huge quantities, roughly in a 1:1 ratio with Cs-137 at the time of the accidentwhoi.edu. Thus, whenever scientists found Cs-134 in post-2011 samples, they could confidently attribute it to Fukushima. As WHOI marine chemist Ken Buesseler explains: “Cesium-134 does not occur naturally…and has a half-life of just two years. Therefore the only source of this cesium-134 in the Pacific today is from Fukushima.”whoi.edu. This isotopic signature was instrumental in, for example, distinguishing the source of the 2014 offshore detections – the coexistence of Cs-134 and Cs-137 at the exact ratio expected from Fukushima decay proved the origin was the Japanese reactor plume, not leakage from any local legacy waste.

In contrast, radioactive leakage from the Farallon Islands dump would likely manifest in different ways. The Farallon barrels contained a mix of isotopes from the 1940s–60s, including activation products and transuranics that have very different signatures from Fukushima fission products. Cesium-137 could be released from Farallon waste (since some medical or research waste might have contained Cs), but crucially there would be no Cs-134 accompanying it (any Cs-134 in those barrels decayed to nothing decades ago). Also, one would expect plutonium and americium isotopes in any leakage from the barrels, whereas Fukushima’s releases of plutonium were negligible outside the reactor vicinity. As discussed, studies of fish near the Farallones did find plutonium and americium at unusual ratios, indicating a local source. By contrast, Fukushima contamination in fish or water shows the hallmark Cs isotopic ratio but no uptick in transuranics far from Japan. Another comparative metric is the ratio of Cesium-137 to Strontium-90; nuclear fuel wastes (like some material possibly in the dump) and global fallout have different Cs:Sr patterns than Fukushima’s waterborne releases. In short, modern scientific techniques (gamma spectroscopy, mass spectrometry) allow analysts to distinguish Pacific radionuclide sources with high confidence. For example, if a coastal seawater sample showed Cs-137 without Cs-134, but also trace Pu-238, one might suspect Farallon leakage or legacy bomb test fallout rather than Fukushima. On the other hand, the detection of Cs-134 alongside Cs-137 is unambiguous evidence of Fukushima. This was the case when unusual radiation readings were obtained on California beaches in the years after 2011 – once tested, they showed radionuclides incompatible with Fukushima’s signature.

Claims of Cover-Up or Misattribution: In the wake of Fukushima, West Coast public concern about radiation spiked, and with it came theories that some contamination was being misattributed. One claim circulated in fringe discussions is that radiation detected on the California coast was not from Fukushima at all, but from leaking barrels at the Farallon Islands – and that authorities were allegedly “covering up” local pollution by blaming Fukushima. At first glance, this idea arose because any detection of radioactivity post-2011 tended to be automatically linked to the much-publicized Fukushima disaster. When higher-than-usual Geiger counter readings were found, some wondered if perhaps the long-forgotten Farallon dump was actually the culprit. A concrete example occurred in early 2014: a YouTube video went viral showing elevated radiation on a beach in Half Moon Bay, CA, sparking fears of Fukushima fallout on California shores. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) investigated, and their analysis determined the readings were due neither to Fukushima nor the Farallon dump – but rather to naturally occurring radioactive minerals in the sand (concentrations of thorium and radium-bearing grains, a type of NORM). In the course of that incident, a local marine biologist speculated to media that “if there is radiation [on the beach] it is more likely due to the radioactive waste dump off the Farallons than it is Japan”, noting that the Farallon site is marked on nautical charts and much closer than Japan. However, subsequent testing disproved the Farallon connection in that case – no cesium was found, only naturally occurring isotopes. The episode is illustrative: concerns about Farallon-sourced radiation are not entirely far-fetched, but they must be backed by isotope evidence. To date, no monitoring program has found evidence that the Fukushima plume was used to “mask” a leak from the Farallon barrels. On the contrary, the distinctive isotopic signals make such a deception unlikely to succeed scientifically. If Farallon barrels were hemorrhaging radioactivity at levels significant enough to register on coastal Geiger counters, one would expect to find plutonium, americium, or perhaps old-generation fission products (like ruthenium-106 or strontium-90) in the mix – none of which have been reported in unusual concentrations post-2011. Instead, the trace radioactivity documented in California seawater, kelp, and biota since 2011 has consistently matched Fukushima’s fingerprint (e.g. the presence of Cs-134, and the specific ratio of Cs-137 to Cs-134) and has been at levels far too low to pose a health riskwhoi.edu.

It is worth noting that while government agencies have been transparent about Fukushima monitoring results, critics point out that long-term studies of the Farallon dump itself have been limited, possibly due to the difficulty and expense of deep-ocean surveys. This gap sometimes fuels speculation of a “cover-up,” but more often it is a question of prioritization: the Farallon site is recognized as a pollution legacy, but it is relatively stable and remote, whereas Fukushima’s impacts were an emergent situation drawing immediate attention. The idea that Fukushima’s fallout “contaminated the entire Pacific,” which gained traction in alarmist social media posts, has been debunked by oceanographers – yes, the Fukushima radionuclides dispersed widely, but the Pacific’s sheer volume ensures extreme dilution. Thus, any attempt to blame elevated local radiation on Farallon barrels rather than Fukushima would run counter to the data. In the Half Moon Bay case, for example, Dan Sythe, a radiation detection expert, noted that if Fukushima were to blame, “the sand would show cesium-137 … Instead [the sample] had radium and thorium”. In sum, no credible evidence has emerged of a deliberate misattribution or cover-up regarding radiation sources; scientists are actively distinguishing and tracking both the Fukushima plume and any legacy sources. Both issues underscore the importance of robust, transparent monitoring of ocean radioactivity.

Conclusion: The U.S. Navy’s admitted dumping of nuclear waste near the Farallon Islands stands as a stark historical reality – one that remained semi-obscured for decades and only fully came to light through declassified records and scientific inquiry. The dumpsite’s existence has inevitably invited comparison with newer radiological events like Fukushima. Careful analysis reveals that the two sources are quite different in both origin and impact. The Farallon Islands dump is a concentrated point source of long-lived radionuclides resting on the seafloor of a marine sanctuary; its risks are localized and chronic (leaching slowly over time, with potential for hot spots in sediments or bioaccumulation in certain species). Fukushima, in contrast, was an acute disaster that released a pulse of radioactivity that dispersed across the ocean; along the California coast its residue has been dilute and is identifiable by short-lived isotopic tracers. While some have speculated about cover-ups, the scientific record – backed by primary sources, government documents, and peer-reviewed studies – indicates that we can and do differentiate Fukushima’s effects from our own nuclear waste legacy. Both, however, serve as reminders of humanity’s nuclear footprint on the ocean. Maps of the Farallon dumping grounds【58†】 and isotopic analyses stand as documentation of past actions that modern society must continue to monitor. The story of the Farallon barrels is entwined with secrecy and Cold War exigencies, whereas the story of Fukushima is one of natural disaster compounded by technological failure – yet both drive home the same lesson: the ocean is not an inexhaustible dumping ground, and what we put into it (deliberately or accidentally) can remain for generations. By investigating these issues with scientific rigor and transparency, we move toward ensuring that the true state of our ocean – and any threats to public health – are fully understood and never hidden.

Sources:

- Office of Radiation Programs, U.S. EPA (1980). “Radioactive Waste Dumping Off the Coast of California” (EPA Fact Sheet)commons.wikimedia.org.

- U.S. Navy (NAVSEA) (2004). “Historical Radiological Assessment, Vol. II – Hunters Point Shipyard (1939–2003)”.

- USGS & NOAA studies (1990s), e.g. H.A. Karl et al. (1994) acoustic mapping of Farallon dump; D.G. Jones et al. (2001) seafloor radiometry surveypubs.usgs.govpubs.usgs.gov.

- T.H. Suchanek et al. (1996). “Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site” Health Physics 71(2):167-178.

- KQED (Apr 2015), “Bleak and Menacing History of SF’s Farallon Islands”.

- SF Public Press (Oct 2022), “Shuttered Radiation Lab…Hunters Point” (Exposed series).

- Patch (Jan 2014), “Beach Radiation Not From Fukushima, Officials Say”.

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (2014–2019) – Ken Buesseler, Our Radioactive Ocean project updates and FAQswhoi.eduwhoi.edu.

- WHOI Press Release (Nov 10, 2014), “Fukushima Radioactivity Detected Off West Coast”whoi.eduwhoi.edu.

- California Coastal Commission (2014) report on Fukushima radiation in the ocean. (Plus additional references as cited inline.)