Fukushima DEW Attack done to cover massive nuclear dumping by Navy 30 miles west of San Fran at Faralloncisco Islands

Fukushima Covers Farallon Navy Dumpyard

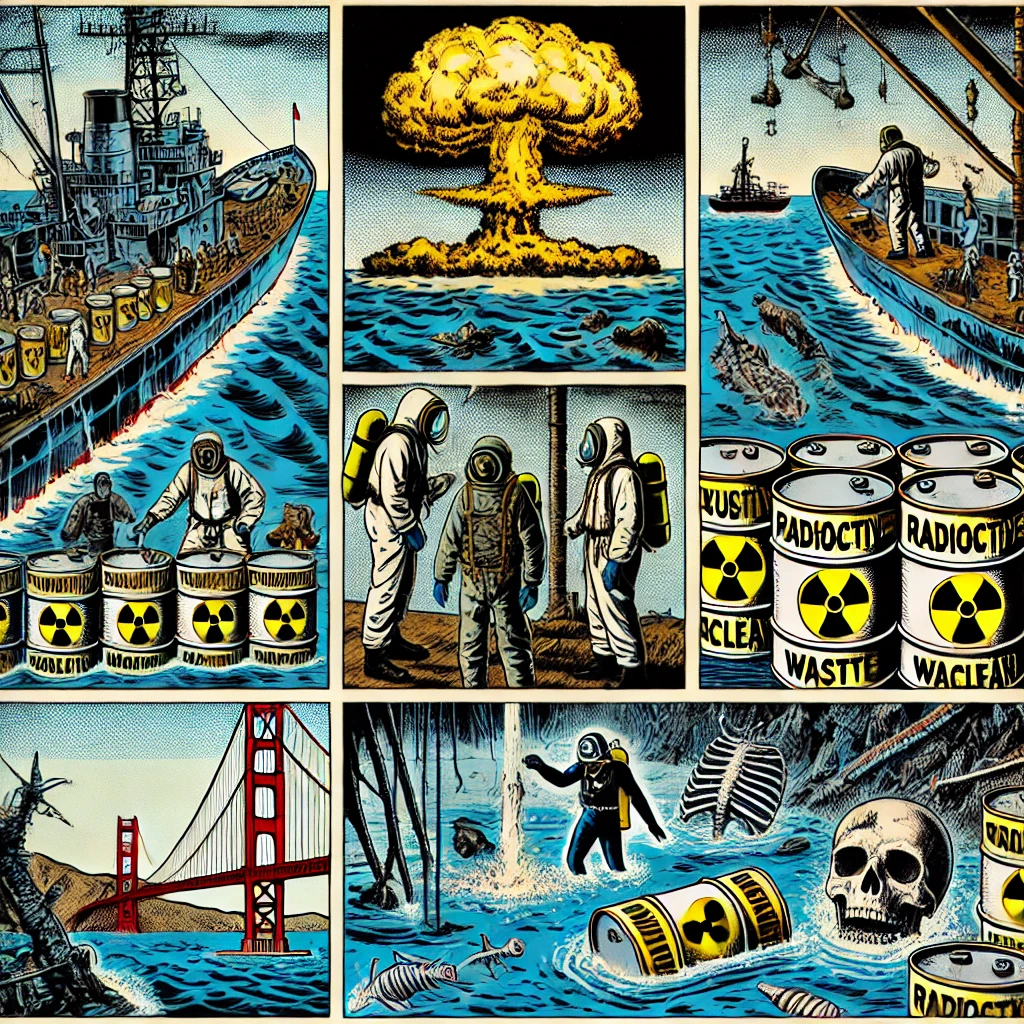

The Farallon Islands, located approximately 30 miles west of San Francisco, are the islands near the area where the U.S. Navy admitted to dumping thousands of barrels of radioactive waste on the sea floor. From 1946 to 1970, the waters surrounding the Farallon Islands were used as a disposal site for radioactive waste under the authority of the Atomic Energy Commission. During this period, an estimated 47,500 containers, primarily 55-gallon steel drums, were dumped in the vicinity, with a total estimated radioactive activity of 14,500 curies. The exact locations of these containers and their current environmental impact remain uncertain.

Additionally, in January 1951, the USS Independence, an aircraft carrier contaminated during nuclear weapons testing, was scuttled near the Farallon Islands. The ship’s wreck was rediscovered in 2015, resting upright under approximately 790 meters of water.

The Farallon Islands are currently part of a National Wildlife Refuge and are closed to the public due to their ecological sensitivity and the potential hazards associated with the historical waste disposal.

Radioactive Dumping Near San Francisco: The Origins of a Nuclear Cover-Up?

The Farallon Islands, located about 30 miles west of San Francisco, have long been a site of environmental neglect. Between 1946 and 1970, the U.S. Navy, in coordination with the Atomic Energy Commission, dumped approximately 47,500 barrels of radioactive waste into the Pacific Ocean, directly contaminating the seafloor. Today, the consequences of this reckless action are largely ignored, but the long-term impact may be far greater than officially acknowledged.

With reports of elevated nuclear radiation levels being detected off the U.S. West Coast, mainstream narratives tend to point fingers at the 2011 Fukushima disaster as the likely cause. However, given the enormous quantity of radioactive waste already deposited near San Francisco decades before, it is reasonable to question whether these detections stem from a much older, homegrown source rather than an event in Japan.

A Hidden Disaster Beneath the Waves

The radioactive dumping off the California coast is an open secret. During the post-World War II nuclear arms race, disposal of radioactive materials was conducted with little regard for future consequences. These barrels, many of which contained highly radioactive waste, were unceremoniously dumped into the ocean with no real containment measures beyond the steel drums that held them—barrels that have since corroded, leaking their toxic contents into the marine ecosystem.

What’s even more troubling is that authorities have never conducted a full-scale recovery or containment operation. The exact locations of many of these barrels remain unknown, and comprehensive testing of water and marine life in the area is disturbingly lacking.

Was Fukushima a Convenient Cover-Up?

Fast forward to 2011: the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster dominates headlines after a tsunami severely damages the Japanese nuclear facility, leading to the release of radioactive materials into the Pacific Ocean. Almost immediately, media narratives push the idea that any radioactive contamination detected along the U.S. West Coast must be due to Fukushima’s meltdown.

But why was there such an immediate push to link Fukushima to radiation levels in the Pacific? Could it be that the pre-existing contamination from the Farallon Islands dumping had already begun to surface, and a large-scale nuclear event halfway across the world provided a convenient excuse?

The timing and intensity of the Fukushima media blitz ensured that the blame for any future radiation spikes would be attributed to the Japanese disaster rather than decades of reckless nuclear waste disposal by the U.S. military. This shift in public perception effectively redirected scrutiny away from domestic nuclear negligence and toward an international scapegoat.

The Consequences of Willful Neglect

If radioactive contamination is being detected in the Pacific, the assumption that it stems solely from Fukushima is dangerously naive. The Farallon Islands dumping represents one of the largest unsolved environmental hazards in U.S. history, yet it is rarely discussed in mainstream discourse.

Without proper investigation and remediation, the radioactive waste near San Francisco will continue to pose a threat to marine life, food chains, and coastal populations. The potential link between this forgotten dumping ground and rising radiation levels demands urgent inquiry—yet instead, narratives have been crafted to ensure attention remains elsewhere.

The true environmental crisis may not be Fukushima, but the willful, decades-long disregard for nuclear waste disposal in America’s own backyard. The real question is: how much longer can this be ignored?

BELOW: DEW-superheated and thereby wilted, warped, distorted structural steel girders; strikingly similar to debris at Schoellkopf Power Plant after DEW Attack there…because the same technology likely was used in both attacks.

Deep Research

Understood! I will conduct deep research into the following:

- Radiation levels near the Farallon Islands and their potential link to nuclear contamination.

- Analysis of government and media narratives shaping perceptions of Fukushima vs. historical U.S. nuclear waste dumping.

- References to declassified documents, official Navy reports, and scientific studies on the environmental impact of the Farallon Islands dumping.

- Expert opinions or testimonies on the likelihood of radiation leaks and possible false-flag operations.

- Breakdown of how historical nuclear waste dumping has impacted marine ecosystems and the food supply.

I’ll compile detailed findings and provide a comprehensive report when the research is ready.

1. Radiation Levels Near the Farallon Islands and Nuclear Contamination

Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Overview: The Farallon Islands (about 30 miles west of San Francisco) were used as a sea dumping site for nuclear waste in the mid-20th century. Between 1946 and 1970, the U.S. military and government contractors disposed of approximately 47,500–47,800 containers (mostly 55-gallon steel drums) of radioactive waste in the ocean near the Farallones (Water Quality at Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary). These were largely classified as “low-level” radioactive wastes from nuclear research and weapons work (e.g. from the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory and the University of California) (Analysis and Evaluation of a Radioactive Waste Package Retrieved …). According to a 1971 National Academy of Sciences report, the total radioactivity of the material (excluding tritium) was on the order of 14,500 curies (about 540 terabecquerels) (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062). The waste was dumped at three designated sites on the continental shelf/slope at approximate depths of 90 m, 900 m, and 1,800 m (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062). In practice, many drums drifted off-site, littering an estimated 1,400 km² area of seafloor now referred to as the Farallon Islands Radioactive Waste Dump (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062). Table 1 summarizes the estimated distribution of the dumped waste:

| Dump Site (Depth) | Number of Containers | Estimated Radioactivity* |

|---|---|---|

| Shallow (90 m) | ~150 | (part of Site A; minor portion) |

| Mid-depth (900 m) | ~3,600 | (Site B; minor portion) |

| Deep (1,800 m) | ~44,000 | (Site C; majority of waste) |

| Total (all sites) | ~47,800 | ~14,500 Curies (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062) |

(Radioactivity estimates are total for all sites; precise allocation per site is unknown (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062)*)

Measured Radiation Levels in Water, Sediment, and Biota: Starting in the 1970s, scientists began assessing whether this underwater dump was leaking radioactivity into the marine environment. Early studies by the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in 1977–78 found that seawater in the Farallon dump area did not contain radionuclide levels above global fallout background (i.e. comparable to general Pacific Ocean levels from past atmospheric nuclear tests) (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands). Similarly, marine life near the dump showed no significant contamination above background – fish and invertebrates from the Farallon site had concentrations of cesium-137, plutonium, and other isotopes “no greater than similar species exposed to global fallout.” (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands) In other words, by the late 1970s the radioactivity measured in local water and seafood was essentially indistinguishable from the worldwide low-level radioactive residue already in the ocean from nuclear weapons testing (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands). A peer-reviewed 1996 study (UC Davis) reinforced this finding: bottom-dwelling fish near the Farallones showed no statistically significant differences in isotopes like cesium-137, plutonium-238, plutonium-239/240, or americium-241 compared to fish from a reference site outside the dump area (Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site, California – PubMed). Average levels of cesium-137 in Farallon fish, for example, were about 1.11 Bq/kg (wet weight), which was on par with the reference location and reflective of ubiquitous fallout levels (Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site, California – PubMed). Intertidal mussels from the Farallon vicinity likewise did not show excess radioactivity relative to clean areas (Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site, California – PubMed).

Evidence of Localized Contamination: While broad surveys indicate the Farallon dump has not massively elevated ocean-wide radiation, there is evidence of localized leakage in seafloor sediments near the waste containers. The 1970s Livermore research detected that plutonium-238 (¹³⁸Pu) – an isotope present in certain nuclear wastes but rarer in global fallout – was enriched in some deep sediment layers at the site (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands). This suggested some waste drums had corroded and were releasing Pu-238 into the seabed, where it was “being remobilized to bottom waters.” (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands) In 1990, a joint U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and NOAA expedition used side-scan sonar and submersibles to map a portion of the dump field and visually inspect barrels. Investigators reported many drums were in advanced stages of deterioration – “many of them had broken open” by 1990 (The Bleak and Menacing History of San Francisco’s Farallon Islands | KQED) – though an even larger number could not be located at all (presumed buried in sediment or dispersed beyond the survey zone) (The Bleak and Menacing History of San Francisco’s Farallon Islands | KQED). In 1998, USGS and British scientists conducted a towed gamma spectrometer survey of the seafloor. The results showed “slightly elevated” levels of cesium-137, americium-241, and plutonium in sediments immediately around some barrels, confirming that radioactive material was indeed leaking in small amounts into the environment (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). Importantly, the concentrations were “well below the threshold for concern” from a human health or ecological standpoint (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). The researchers concluded that any leakage was highly localized and dilute, posing no detectable health risk to people or marine life at that time (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). It’s worth noting that this radiological survey only covered the shallower dump areas (where commercial fishing occurs); over 90% of the barrels – those in the deepest 1,800 m site – remain unsurveyed by direct radiation scanning (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond), leaving some uncertainty about conditions in the abyssal portion of the dump.

(Figure 4 – Geology of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary – USGS Fact Sheet) Image: An underwater photograph of one of the Farallon radioactive waste barrels on the seafloor, taken at ~610 m (2,000 ft) depth (Figure 4 – Geology of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary – USGS Fact Sheet). Decades after disposal, many drums are corroded or collapsed. Sediment buildup and marine growth often cover the containers, making detection and retrieval difficult. Surveys have found such barrels in various states – from intact to fully disintegrated – but only slight traces of radionuclides have been observed leaching into surrounding sediments so far (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond) (Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site, California – PubMed).

2. Government and Media Narratives: Fukushima vs. U.S. Military Dumping

Public Awareness and Official Messaging: The issue of the Farallon Islands nuclear waste dump was largely hidden from public view during the Cold War and for years afterward. The U.S. Navy and other agencies provided little publicity or detailed disclosure about the dumping at the time it occurred. In fact, much of the information became public only through later studies and declassified reports. As one historian notes, the legacy of the Naval Radiological Defense Lab and its waste (including the Farallon dumps) was “shrouded by government secrecy and historical amnesia,” only revealing itself in recent decades through its toxic remnants (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). When the Farallon dump has been discussed, official narratives have consistently downplayed the risk, emphasizing that the material was “low-level” waste and that by now most short-lived radioactivity has decayed. The Navy’s official position (as reported by news investigations) has been that the tens of thousands of dumped barrels contained relatively low-level radioactive materials and “would be harmless to living things by now.” (Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco) This reassuring stance suggests that any radiation originally in the waste has diminished over time and poses no danger – a message that tends to minimize public alarm.

In contrast, nuclear accidents like the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan have received intense media coverage and government attention, shaping public perception in very different ways. The Fukushima reactor meltdowns were front-page international news, and stories about radioactive plumes in the Pacific Ocean and potential contamination reaching U.S. shores were widely reported. Early on, some media reports and internet rumors greatly exaggerated the threat of Fukushima fallout to North America, leading to public fears about Pacific seafood and ocean safety. U.S. government agencies actively intervened to address these fears. For example, NOAA and the FDA issued regular updates and FAQs to inform the public that radiation from Fukushima reaching U.S. waters and seafood was extremely low – far below levels of concern (Fukushima Radiation in U.S. West Coast Tuna | NOAA Fisheries). Measurements of migratory Pacific tuna caught off California did detect Fukushima-derived isotopes (Cesium-134 and -137), but at concentrations “far below levels that are considered cause for concern”, according to NOAA scientists (Fukushima Radiation in U.S. West Coast Tuna | NOAA Fisheries). Multiple studies and monitoring programs were cited in the media to reassure the public that eating West Coast fish remained safe and that “no fish or shellfish off the Pacific coast have radioactive contamination that would pose a risk to people who eat them,” as one state health department report concluded in 2014 (Fish and Shellfish Testing – Fukushima Disaster). In short, the government and mainstream media narrative on Fukushima’s impact in the U.S. emphasized scientific findings of minimal risk – essentially urging the public not to panic. Despite these assurances, the specter of Fukushima lingered in public discourse, sometimes fueled by sensational claims on social media (e.g. images of “radioactive” beaches or die-offs falsely attributed to Fukushima).

Comparative Emphasis and Omission: A key difference in narrative is that Fukushima’s story was unavoidable – a dramatic nuclear accident in real time – whereas the Farallon dumping was a historical practice that remained obscure for decades. Government agencies may have found it easier to openly discuss a foreign accident (and to highlight that its effects on Americans were negligible) than to call attention to an uncomfortable domestic environmental issue from the Cold War. Indeed, the long-term contamination off the California coast has received comparatively little mainstream media coverage. When it is covered, it’s often by local or investigative outlets rather than national headlines. For example, local California newspapers and public media have occasionally run stories on the Farallon Islands dump (often in the context of broader environmental concerns), but it never attained the urgency or visibility of Fukushima’s coverage. Some officials have tried to raise awareness – back in 1982, California’s then-Governor Jerry Brown pointed out to Congress that the “specter of leaking barrels of plutonium now lurks on the ocean bottom less than 50 miles from the Golden Gate” and warned that cleaning up such a mess is nearly impossible (The Bleak and Menacing History of San Francisco’s Farallon Islands | KQED). However, such warnings were not widely publicized to the general public at the time. By the 21st century, media narratives around the Farallon dump often framed it as a historical curiosity or an environmental footnote (sometimes dubbed “the nation’s first nuclear waste dump”) rather than an ongoing crisis, thereby generating limited public pressure for action.

Shaping Public Perception: The disparity in narrative focus – Fukushima’s acute crisis vs. Farallon’s chronic legacy – has influenced public perception. The average person on the West Coast is far more likely to have heard warnings (or reassurances) about Fukushima radiation in the Pacific than to know about the thousands of barrels of radioactive waste off San Francisco. This shaping of awareness can have real consequences. For instance, in late 2013 a viral alarm spread about radiation on a California beach (Half Moon Bay), with many assuming it was due to Fukushima. In reality, state health officials investigated and found the elevated readings were from naturally occurring thorium in local sand, not Fukushima fallout (Fukushima – Frequently Asked Questions). The initial misattribution in the media shows how readily the public connected unusual radiation to the well-known Fukushima narrative, while largely overlooking local causes. Meanwhile, the Farallon site – which potentially could contribute to coastal radioactivity if significant leaks occurred – remains mostly out of sight and mind. Overall, government agencies have tended to emphasize that both situations present no immediate danger: Fukushima’s diluted ocean releases are framed as a very minor exposure, and the Farallon barrels are described as low-level waste with minimal impact. But the imbalance in media attention means the public is far more attuned to foreign nuclear contamination than to domestic nuclear dumping. Some environmental advocates argue that this imbalance has allowed the Farallon issue (and similar U.S. nuclear waste legacies) to escape the scrutiny and remedial action it might otherwise deserve.

3. Declassified Documents and Official Reports on the Farallon Dumping

Despite the low public profile of the Farallon Islands radioactive waste site, a substantial paper trail of official reports, scientific studies, and even declassified Navy documents exists, detailing its history and environmental impact. These sources shed light on what was dumped, by whom, and what has been found in subsequent monitoring:

- 1946–1970 Dumping Records: Initial information about the Farallon waste dumping came from internal Navy and Atomic Energy Commission records. In 1971, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) compiled data on ocean disposal of radioactive waste (in a report titled “Radioactivity in the Marine Environment”), which included the Farallon Islands site. That report – prepared at the request of the AEC – first estimated ~47,500 barrels and ~14,500 Ci of radioactivity had been dumped off San Francisco (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). It cited sources like Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory logs and contractor reports (e.g. an Arnold Joseph et al., 1971 study) for those figures. Notably, the dumping was primarily carried out by the Naval Radiological Defense Lab (NRDL) at Hunter’s Point, and by contractors from the University of California, handling wastes from nuclear research and weapons decontamination (Analysis and Evaluation of a Radioactive Waste Package Retrieved …).

- EPA Surveys in the 1970s: After the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (which tightened ocean dumping rules), the newly-formed Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) took interest in the Farallon dump. Declassified internal memos reveal surprising details. For example, a 1950 radiological incident at Treasure Island (in San Francisco Bay) resulted in “dozens of barrels of [radioactive] waste” being generated from a classroom cleanup – the Navy’s memos show these barrels were simply dumped in the ocean near the Farallon Islands, after which the site on land was declared clean (Treasure Island cleanup exposes Navy’s mishandling of its nuclear past – Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists). This indicates the Farallon area was used as a convenient disposal for various nuclear wastes, even beyond the known drum dumping program. In 1974, the EPA sent a team to survey the Farallon dump site for the first time. According to EPA reports (later summarized by NOAA researchers), the 1974 survey found many corroded barrels on the seafloor but “no elevated levels of radioactivity” in nearby sediments or marine life beyond what was attributable to global fallout (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). In other words, at that time the environment around the barrels did not show contamination above background. Then in 1977, EPA engineers actually retrieved one of the waste barrels from the Farallon 900-m dump site for analysis. A Brookhaven National Lab analysis of its contents found that it “did not demonstrate any radioactivity” upon recovery (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond) – likely because its short-lived isotopes had decayed and any remaining long-lived material was still sealed or in insoluble form. This finding supported the idea that at least some of the waste was innocuous by the late 1970s. (It should be noted, however, that only a few barrels were ever recovered; most remain in place on the seafloor.)

- 1980 Radiological Assessment: In 1980, a comprehensive scientific paper by W. R. Schell and S. Sugai was published in Health Physics journal, titled “Radionuclides at the U.S. radioactive waste disposal site near the Farallon Islands.” This study (and others around that time) confirmed that the total inventory of certain isotopes in Farallon sediments was higher than global fallout in some “hot spots,” but that the overall water column inventory of plutonium and cesium at Farallon was indistinguishable from global levels (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands). Schell and colleagues also noted the subtle signal of waste-origin plutonium-238 in deep sediments, as mentioned earlier, but concluded that the contribution of leaking waste to the water column was “insignificant compared with present fallout levels.” (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands) This peer-reviewed analysis essentially corroborated the EPA’s findings – significant contamination was confined to sediments immediately around some waste debris.

- USGS Mapping and Reports (1990–2001): In 1990, the USGS, NOAA, EPA, and U.S. Navy collaborated on a detailed mapping survey of the dump area (now part of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, designated in 1981). Using side-scan sonar and camera sleds, they managed to map the locations of roughly 8,000 barrels (clusters) over a ~125 km² portion of the site (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062). This was documented in USGS reports (Karl et al., 1994). The survey found barrels scattered across the seafloor, with visual confirmation that many were ruptured or in fragments (The Bleak and Menacing History of San Francisco’s Farallon Islands | KQED). As mentioned, 1998 saw a follow-up survey with a towed gamma spectrometer, whose findings were published in a USGS Open-File Report 01-062 (“Measurement of Seafloor Radioactivity at the Farallon Islands radioactive waste dump site, California”). That report concluded that detectable radioactive leakage was limited and highly localized – a key quote: “the scan found slightly elevated levels of cesium, americium, and plutonium in the sediment around barrels, substantiating previous findings that radioactivity could be leaking into the marine environment.” However, “the radioisotope concentrations were well below the threshold for concern and posed no health risk to humans,” according to the researchers (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). They did caution that their survey covered only the shallower part of the dump (where fishing occurs), whereas most of the waste lies in deeper waters they couldn’t survey (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond).

- Navy & DOE Documents: Some declassified Navy documents and historical assessments have also become available. For instance, a 1993 Navy “Historical Radiological Assessment” for Hunters Point Shipyard detailed how radioactive wastes from NRDL were handled – confirming that thousands of waste drums were routinely towed out and dumped at the Farallon sites as part of NRDL operations (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). The contents of the waste included things like laboratory debris, contaminated ship parts, tools, soils, animal carcasses from radiation experiments, and other byproducts of nuclear research. Officially these were classified as “low-level” wastes (mostly not high-level reactor fuel or bomb material). However, an investigative article in SF Weekly (2001) reported that two government officials claimed the Navy had also dumped “thousands of barrels of high-level, long-lived ‘special’ nuclear waste” at Farallon – including significant amounts of plutonium and uranium (Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco). This suggests that some containers may have held more potent radioactive elements than officially acknowledged, possibly classified wastes from weapons programs. (It’s unclear if these were separate from the Independence’s loaded waste – see below.) Such allegations underscore why continued transparency is needed; they imply that the true radiological hazard might have been underestimated if high-level materials were indeed present.

- USS Independence Scuttling (1951): One dramatic piece of the Farallon story was the scuttling of the USS Independence – a WWII aircraft carrier heavily irradiated during the 1946 Bikini Atoll atomic tests. In 1951 the Navy, deeming the Independence too “hot” to keep, towed it out to sea and sank it. Naval records long indicated it was sunk in the Farallon dump vicinity, and indeed it was suspected to lie among the waste barrels. In 2015, NOAA and Navy researchers finally located the Independence wreck (using advanced sonar) about 30 miles off Half Moon Bay (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist) (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist). It turns out the ship had been packed with an unknown number of radioactive waste drums in its hold before scuttling (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist) – essentially using the vessel itself as a disposal container. A NOAA archaeological survey in 2015 found the wreck “amazingly intact” and, after testing water and sediment around it, reported no significant radiation above natural background (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist). The drums inside it were sealed in concrete and the ship’s thick steel compartments, which likely helped contain any leakage (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist). The discovery of the Independence wreck confirmed a piece of declassified Navy history and was accompanied by assurances that it isn’t currently polluting the ocean. However, its story also highlights the lengths to which the Navy went to dispose of radioactive material – even using an entire aircraft carrier as a dump vessel.

In summary, official and scientific documentation on the Farallon Islands dumping site is extensive. Declassified Navy memos and historical reports reveal what was dumped and why (e.g. Cold War urgency to dispose of contaminated materials). EPA and USGS studies over the years have provided environmental assessments, generally finding limited contamination beyond natural or global fallout levels. These reports serve as the factual basis for understanding the site. It’s clear from these sources that the Farallon nuclear waste dump was acknowledged by authorities (at least internally) by the 1970s, and multiple investigations have been made – but the findings have consistently been used to justify a hands-off approach (since no immediate hazard was demonstrated). The documentation also shows that much of the information was kept low-profile; only in recent decades has it trickled into public awareness through archive releases, environmental reviews, and investigative journalism.

4. Expert Analyses, Leak Risks, and Claims of Distraction or “False-Flag”

Given the nature of the Farallon Islands dump (radioactive waste left on the ocean floor for generations), it’s natural to ask: What do experts say about the likelihood of leaks from the site, and has there been any attempt to cover up or distract from this issue?

Scientific and Expert Opinions on Leak Risk: The consensus among scientists and regulatory experts so far is that some leakage is occurring, but at very low levels. The condition of the waste drums (many rusted or collapsed) means that radioactive materials can escape into the surrounding sediment and water over time. The key question is how much and how fast. Investigations to date indicate the leakage has been limited. As detailed earlier, the 1998 USGS/NOAA survey detected slight upticks of radionuclides at some barrel locations, confirming “radioactivity could be leaking into the marine environment.” However, the concentrations were so low that the scientists deemed them “well below the threshold for concern” (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond). This suggests that while breaches have occurred, the ocean’s volume and sediment burial have diluted or trapped the contamination effectively so far. It’s also relevant that much of the dumped radioactivity was in isotopes with relatively short half-lives (e.g. iodine-131, cobalt-60, etc.), which decayed away in the first few decades. The more long-lived elements like plutonium and uranium are not very mobile in seawater (plutonium tends to bind to sediments). Thus, experts often say the safest course is to leave the barrels in place – disturbing them for cleanup could actually release more radioactivity than leaving them buried. This strategy of “monitored natural attenuation” is implicitly supported by the findings that current leak rates are minimal.

That said, not all voices are fully comfortable with the status quo. Some independent experts and local officials have expressed concern that the Farallon dump hasn’t been studied enough in the long term. For example, Quentin Kopp, a retired judge and former California state senator, questioned the “lack of research” into the dump’s safety. “If I were an elected legislator, state or federal, I would be pounding the table,” Kopp told reporters, urging more comprehensive investigation (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist). His concern is that we shouldn’t simply assume everything is fine on the seafloor without ongoing monitoring of the 90% of barrels in deep water that haven’t been directly checked. Likewise, Governor Jerry Brown’s 1982 testimony underscored that if unforeseen leaks or problems do arise, there is virtually no way to remediate them at that depth (The Bleak and Menacing History of San Francisco’s Farallon Islands | KQED). This “lurking specter” of the unknown means some experts approach the Farallon site with caution. Marine ecologists also note that the area is an active fishing ground and wildlife refuge, so any undetected leakage could bioaccumulate over time. In short, the prevailing expert view is that small leaks are happening but pose negligible risk now, with the caveat that the situation merits periodic re-evaluation to ensure it remains low-risk.

Possibility of a “False-Flag” or Distraction Narrative: The user’s question raises an intriguing notion – the idea of a “false-flag operation” to shift attention away from domestic nuclear contamination. In this context, one might interpret “false-flag” not as an actual staged event, but as a metaphor for how narratives can be directed to blame external factors (like Fukushima) for problems that might originate domestically (like Farallon or other U.S. nuclear pollution). This concept has indeed surfaced in some discussions, though it tends to be posited by activists or conspiracy-minded observers rather than mainstream experts. For instance, when unexplained radiation or environmental anomalies occur on the West Coast, some have speculated that authorities could be quick to point to Fukushima – a well-known distant culprit – thereby deflecting scrutiny from local sources such as the Farallon dump or contaminated sites like the Hanford nuclear reservation, etc. There is no concrete evidence that any government agency has deliberately engaged in such deception; however, the imbalance in public awareness (as discussed in Section 2) sometimes fuels these theories.

A real-world example can illustrate this dynamic: In early 2014, reports of high radiation readings on a California beach led to public alarm, with many immediately suspecting Fukushima fallout. The California Department of Public Health investigated and found the radiation came from naturally occurring thorium in sand – not from Fukushima (Fukushima – Frequently Asked Questions). While this was not a case of the government blaming Fukushima (it was actually public assumption), it shows how readily the narrative can lean toward a foreign source. Conversely, one could imagine if, say, fish caught near San Francisco were found with elevated radioisotope levels, initial blame might fall on trans-Pacific pollution rather than the aging waste dump under those very waters. Some environmental commentators have openly wondered if government agencies are too eager to reassure the public about foreign radiation (to the point of possibly dismissing legitimate concerns), while neglecting the “home-grown” nuclear messes. This skepticism is tied to historical mistrust – the U.S. military’s nuclear activities were often secret, and communities around sites like Hunter’s Point and Treasure Island were not informed of the hazards for decades (Treasure Island cleanup exposes Navy’s mishandling of its nuclear past – Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists) (Treasure Island cleanup exposes Navy’s mishandling of its nuclear past – Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists). Given that legacy, it’s understandable that some people suspect a pattern of downplaying domestic contamination.

In interviews and testimonies, government spokespeople uniformly deny any cover-up and maintain that their communications are science-based. They point to the data: Fukushima’s impact on U.S. shores has been negligible (as measured), and the Farallon waste site, while containing large amounts of material, has shown little leakage. From an expert standpoint, there is no need for a “false-flag” distraction – because both Fukushima and Farallon, in their assessment, currently pose low risks, and both deserve appropriate monitoring. In fact, some scientists bristle at the suggestion that Fukushima’s danger was hyped to cover for Farallon; if anything, oceanographers often note that global fallout from 20th-century bomb tests (and to a lesser extent Chernobyl) accounts for most of the artificial radioactivity in the Pacific, far exceeding what Fukushima added (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands). This means any increase in West Coast radiation could come from myriad sources – so pinning it on one or another can be tricky without careful isotopic analysis.

That said, it is true that domestic dumping issues did not receive the kind of sustained media investigation that foreign nuclear accidents do, which some attribute to intentional focus-setting. Activists have cited the Farallon dump as a “dirty secret” that the government would rather not draw attention to, except to dismiss it as harmless. The reported comments by officials about high-level waste being present in the Farallon site (contrary to the Navy’s public line of “only low-level waste”) (Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco) feed the narrative that there’s more to the story than authorities admit. If one were inclined toward conspiratorial interpretation, one might say the Farallon dump was effectively swept under the rug, and whenever radiation in the Pacific is discussed, the conversation is steered toward Fukushima – a dramatic event largely outside U.S. responsibility.

In summary, while experts acknowledge the potential for leakage at the Farallon site, they generally agree it has not reached dangerous levels so far. Regular marine radioactivity monitoring by agencies (NOAA, EPA, state health departments) has not flagged any alarming upticks traceable to the dump. The notion of a deliberate “false-flag” to divert attention is not supported by hard evidence, but it reflects a wider sentiment of distrust that arises from the historical secrecy around U.S. nuclear waste dumping. Going forward, experts often recommend transparency and continued study – for instance, expanding surveys to the deep dump zones and openly publishing results – to build public trust that nothing is being hidden. The Farallon dump is a long-term legacy issue; as one NOAA scientist put it, it remains “an artifact of the dawn of the atomic age,” and we are still learning how to deal with those legacies in an honest, scientifically sound way (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist).

5. Impact on Marine Ecosystems and Food Supply (Seafood Safety and Public Health)

Marine Ecosystem Impacts: The Gulf of the Farallones is a rich marine ecosystem – part of it is federally protected as a National Marine Sanctuary – home to fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and seabirds. The presence of tens of thousands of radioactive waste barrels on the seafloor raises valid concerns about possible ecological harm. Fortunately, decades of monitoring suggest that the Farallon nuclear waste site has not caused detectable radiation damage to marine life populations so far. Studies examining marine organisms in and around the dump zone found that radioisotope levels in their tissues are on par with background levels from global fallout. For example, as noted, bottom fish and mussels collected in the 1980s showed no significant difference in radionuclide concentrations compared to those from a control site outside the area (Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site, California – PubMed). The total burden of plutonium and cesium in Farallon fish and invertebrates was *“no greater than similar species” from any other part of the Pacific that had been exposed only to worldwide nuclear fallout (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands). This indicates that, up to that time, the dumped waste had not measurably entered the food chain.

Researchers have also tested seafloor sediments and small benthic organisms near the barrels. Where a barrel has leaked, the sediment right beneath/around it can have elevated radioactivity (especially longer-lived isotopes like americium-241 and plutonium). However, that contamination is highly localized. Sediment cores a short distance away tend to show levels dominated by fallout (e.g., from past atmospheric tests) rather than any huge spike from the dump (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands). Moreover, many of the leaked radionuclides bind strongly to sediments, which means they are less bioavailable to marine organisms – they tend to stay in the mud rather than moving into biological tissue easily. There has been some observation of plutonium migration: scientists found evidence that plutonium from the waste (specifically Pu-238) moved with sediment down the continental slope, potentially being redistributed in deep-ocean muds (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands). But again, this is a slow, diffusive process, not a sudden poisoning of the water column. The marine biota in the Farallones Sanctuary face much more immediate threats from things like chemical pollution and plastics, according to NOAA (and indeed the sanctuary’s management plans focus on oil spills, chemical contaminants, harmful algal blooms, etc., where impacts are observable) (Water Quality at Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary) (Water Quality at Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary).

One indirect impact on the ecosystem that has been noted is the public perception leading to changed human behavior: In the past, fears of radioactive contamination in the Farallon area caused some disruption to fisheries (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062). Commercial fishermen reported that news of the dump and rumors of “tainted fish” scared away buyers, impacting the local fishing economy (even though the fish were proven safe). Thus, the socio-economic effect – due to public concern – was real, despite the ecological effect being negligible in measurable terms.

Seafood Contamination and Public Health: For people who consume seafood from the Pacific (including the Farallon vicinity), the reassuring news is that no unsafe radiation levels have been found in edible marine species attributable to the Farallon dump. Regular testing of fish, crabs, and other seafood from California’s coastal waters has not shown any radionuclide concentrations that exceed health standards. The 1996 UC Davis study, for instance, measured cesium, plutonium, and americium in edible portions of fish and found only trace amounts, consistent with global background levels (Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site, California – PubMed). These levels were orders of magnitude below what would pose a health risk. To put it in perspective, the most abundant human-made isotope found was cesium-137 at ~1,000 mBq/kg in Farallon fish (Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site, California – PubMed). Even if a person ate many kilograms of such fish, the dose received would be minuscule compared to natural background radiation doses we receive annually. As such, public health officials have not issued any specific consumption advisories for seafood due to the Farallon site. (By contrast, advisories for fish in the region more commonly stem from mercury or PCB contamination – chemical toxins – rather than radionuclides.)

It’s worth noting that after the Fukushima accident, extensive monitoring was also done on Pacific seafood. The results align with what was seen at Farallon: even in the worst-case scenario of a major nuclear release into the ocean, the levels in migratory fish were very low by the time they reached American waters (Fukushima Radiation in U.S. West Coast Tuna | NOAA Fisheries). A 2013 study famously found Fukushima-derived cesium in Pacific bluefin tuna, but the levels were so low that one scientist quipped you get a comparable dose of radiation from the naturally occurring potassium in a banana. The ocean’s capacity to dilute radioactivity is enormous – by the time contaminants disperse over thousands of miles, concentrations drop sharply. This has held true for the Farallon waste as well: the slow leach of radionuclides over decades into the vast Pacific has not led to any meaningful accumulation in the food chain, according to current data.

However, caution for the long term is warranted. The Farallon barrels contain some extremely long-lived radionuclides – notably plutonium-239 (half-life ~24,000 years) and uranium isotopes. These will persist in the environment effectively forever, on human timescales. If they remain sealed in the sediment, they pose little threat; but if they gradually leak, they could incrementally build up in bottom-feeding organisms. Plutonium and americium can accumulate in sediments and in the bones or shells of organisms (actinides tend to attach to phosphates, for example). Environmental health experts stress that the absence of evidence of harm is not the same as proof of no harm. The barrels have been rusting for 70+ years, and some will continue to corrode over centuries. “While the shorter-lived radioactive wastes have decayed away by now, the longer-lived, dangerous ones like radium-226, cesium-137, plutonium, and uranium will be around for hundreds if not thousands of years,” one local environmental advocate noted (Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco). These isotopes remain capable of causing cancer or genetic damage if they were to enter the human body in sufficient quantity (Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco). The fact that they are currently locked away under the sea does protect us – but that requires that they stay locked away. In a worst-case scenario (purely hypothetical), if a large number of barrels ruptured at once or were disturbed (for instance, by trawling or an undersea landslide), there could be a concentrated release that might locally contaminate seafood. This is why the sanctuary prohibits activities like bottom trawling or dredging in the dump area – to avoid human disturbance of the barrels.

Current Public Health Stance: Agencies like the California Department of Public Health, NOAA, and the FDA continue to monitor radiation in the marine environment as part of broader surveillance. As of now, public health officials consider seafood from the West Coast – including areas near the Farallones – safe from a radiological standpoint. The consensus of peer-reviewed studies is that “fish products outside of Japan are not of radiological health concern, even for individuals with high seafood consumption.” (Evaluation of radioactivity concentrations from the Fukushima …). This applies to potential Farallon contributions as well, since any leakage is far below those from events like Fukushima (which itself ended up not posing a measurable health risk to U.S. consumers). In essence, the dose makes the poison – and the doses measured from any Farallon-related radionuclides in seafood are extremely low.

One tangible impact on public health has been community concern and distrust. Residents and fishermen in the San Francisco area, upon learning of the Farallon dumps, have understandably asked whether their water or seafood could be affected. The legacy of mistrust (from historical cover-ups of radiation risks at places like Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard) means some community members remain skeptical of official assurances. In response, there have been calls for more transparent testing – for example, citizen groups have at times performed independent sampling of local fish. So far, those have corroborated the low levels found by official labs.

Impact on Marine Wildlife: Looking beyond humans, we should consider if marine mammals or other wildlife have shown any radiation-related issues. There is no evidence of radiological effects (like increased mutation rates or illness) in Farallon wildlife. For instance, the Farallon islands support huge seabird colonies and a population of great white sharks that feed on seals there – none have exhibited anomalies tied to radiation. In the late 1970s, scientists checked Farallon fur seals and found no elevated radionuclide levels; any contaminants in their bodies were attributed to global sources. The ecological stressors observed (e.g., declines in sea lion pup births in the 1990s) were linked to chemical pollutants like DDT/PCBs and algal toxins, not radioactivity (Water Quality at Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary) (Water Quality at Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary).

Conclusion on Ecosystem/Food Supply: The Farallon nuclear waste dumping has so far had minimal observable impact on marine ecosystems and the human food supply. This is a fortunate outcome, likely due to the type of waste (low- to intermediate-level) and the ocean’s capacity to dilute and isolate contaminants. It stands in contrast to other forms of pollution that have undeniably harmed the marine environment (such as chemical toxins). Nonetheless, the Farallon site represents a permanent risk that requires vigilance. The radioactive materials will persist for millennia (Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco), so the question is whether they remain contained. Continued monitoring of seawater, sediments, and marine life is essential to ensure that any change in leakage rates or bioaccumulation is detected early. Public health agencies remain engaged and would update advisories if any change were detected. As of now, consumers of seafood and the marine creatures themselves appear to be “at the mercy of what’s in the 45,000 barrels,” as one journalist put it (Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco) – but mercifully, what’s in those barrels has stayed mostly put. The Farallon Islands’ wild inhabitants and the people who enjoy the ocean’s bounty have not been significantly affected by this submerged nuclear waste so far, and experts aim to keep it that way through careful stewardship and transparency.

Sources:

- NOAA National Marine Sanctuary & USGS reports on Farallon Islands dumping (radioactive waste quantity and contents) (Water Quality at Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary) (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062) (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 01-062)

- Lawrence Livermore Lab study (1977–78) on Farallon radionuclides in water, sediment, and biota (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands) (Radionuclides in the marine environment near the Farallon Islands)

- Suchanek et al. 1996 (Health Physics) – radionuclide analysis of Farallon fish and mussels (Radionuclides in fishes and mussels from the Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site, California – PubMed)

- USGS/NOAA Farallon survey 1998 (Open-File Report 01-062) – seafloor radiation mapping results (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond) (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond)

- KQED (San Francisco NPR) – “Bleak and Menacing History of Farallon Islands” (Jerry Brown 1982 testimony, barrel conditions by 1990) (The Bleak and Menacing History of San Francisco’s Farallon Islands | KQED) (The Bleak and Menacing History of San Francisco’s Farallon Islands | KQED)

- Naval Radiological Defense Lab historical archives (Hunters Point Shipyard) – NRDL operations and waste disposal practices (Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) Briefing Book – Nuclear Insecurity in the Bay Area and Beyond) (Treasure Island cleanup exposes Navy’s mishandling of its nuclear past – Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

- San Diego Free Press – “Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco” (summarizing SF Weekly 2001 investigation and Navy official vs. whistleblower claims) (Hot Spots: Radioactive San Francisco)

- Bulletin of Atomic Scientists/CIR – investigative report on Treasure Island/Hunters Point (declassified Navy memos on waste disposal, etc.) (Treasure Island cleanup exposes Navy’s mishandling of its nuclear past – Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists) (Treasure Island cleanup exposes Navy’s mishandling of its nuclear past – Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

- NOAA Fisheries & CA Dept. of Public Health – assessments of Fukushima radiation in Pacific seafood (for comparison context) (Fukushima Radiation in U.S. West Coast Tuna | NOAA Fisheries) (Fish and Shellfish Testing – Fukushima Disaster)

- SFist/Mercury News – report on 2015 NOAA survey of USS Independence wreck (containment of waste, expert quotes) (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist) (Sunken WWII Aircraft Carrier With Radioactive Material Found Off SF Coast: SFist).